Elevated by Concrete Sails

/I spoke to a woman this week who was raised in a harbourside suburb of Sydney. Her stories reminded me of some of the mellow enjoyment to be had there on sunny winter days.

I’m not talking about the hours of irritation commuting to work when you live there or the strange and alienating pecking order that drives people to walk into you on the street because they think they are more important than you are. I’m gonna forget about the fact that the overwhelming majority of people who live in Sydney live miles from the harbour. And that even if you only live twenty kilometres from the harbour, it can take you an hour to get there because the traffic and transport are so inefficient and snarly. Most Sydney people might only go there a few times a year.

For now, I’m thinking about the deep green of the clear harbour water under a crystal blue sky. I imagine myself leaning on the bronze harbourside railings as sun shines hard and bright on the glinting cream and white tiles of the Opera House sails. Walking west, the stone plain of the forecourt to the Opera House is a refreshing change from the closed-in city streets. The building itself towers over its steep slabbed steps, like an approach to a temple, the whole creation extending out into the harbour on its own little peninsular.

Behind me the worn sandstone walls of the embanked hill are usually damp. Tiny coral-like orange plants, alongside bright green ferns, stretch out from the cracks in the stone.

The Opera House is built on Bennelong Point, named for the multilingual Dharug man of the same or similar name (1764 - 1813) who became a cultural educator for the founding Governor of the New South Wales colony. Intelligent and funny, Bennelong traveled to England and got stuck there for a couple of years longer than he wanted to. His homesickness was debilitating. Perhaps he learned more than he wanted about the subjugation of his people. In any case he became a violent alcoholic after his return and died a lonely man.

About 170 years later, the first concert on the construction site of the Sydney Opera House was performed by another tragic figure — the magnetic Paul Robeson. You can see a brief recording from the 1960 performance here. It’s worth looking at what the site looked like, as well as to experience again that uniquely charismatic voice. Some great footage of the construction workers’ bums illustrate the editors’ regard for their dignity.

Walking east across the Opera House forecourt one enters the two-hundred-year-old Botanical Gardens cultivated behind hand-hewn stone breakwalls in an area sometimes called Farm Cove. Before that it was Wuganmagulya. Ironically, the British botanists’ park is probably more like pre-invasion Sydney than any other part of the Central city. There was a freshwater creek there in the days of the Gadigal, the original people of the place. Remnants of it persist. Spikes of the flame-like gymea lilies on their 2-metre tall stalks, and spears of centuries-old grass trees frame the view of the Opera House in a context that soothes the spirit.

I was born in 1962, so I grew up surrounded by skepticism, frustration and, conversely, exciting lotteries about the Opera House. Bennelong Point was in a permanent cloud of concrete dust, construction noise and anticip-cip-pation.

Post-invasion Australia was populated by poor and uneducated people who drowned in despair or dreamt of a better life. The Sydney Opera House tells the story of the determination of those dreams, as well as the stubborn resistance of other Australians to the idea that a building constructed for culture could be worthwhile.

The building of an Opera House was first proposed in the 1940’s by a man who loved music above everything. An international competition was held for its design. The Opera House’s construction was planned to take four years, beginning in 1958, but the magnificent group of theatres, transmogrified from its original sleek design, only opened in 1973.

I remember the opening of the Opera House. It was a big excuse to come to town. The Queen came, but we didn’t see her. There were fireworks, only the second time I’d seen them. The first was at the celebrations of the bicentennial of James Cook’s landing in Australia; the drifting giant chrysanthemums of luminosity impressed me for life.

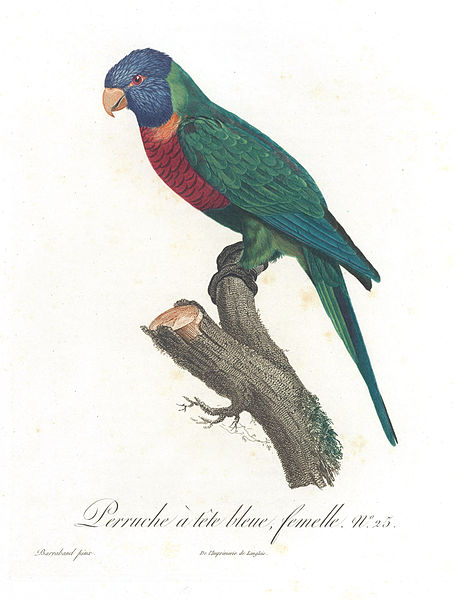

Nowadays, on my fantasy walk harbourside, I would go next to one of the older cafes on the western side of Bennelong Point. I’d order a latte and sip it slowly at a small table overlooking the sparkling water under the Harbour Bridge. You can see tourists in baggy overalls climbing the bridge likediscombobulated centipedes. My mum, who is a marriage celebrant, conducted a wedding up there (surreptitiously — they weren’t given permission to do it). The ferries, the stupid tourist speed boats and slow majestic ships go by. You have to guard your food if seagulls are around — you can see their red feet lit by the sunlight through the canvas sunshade overhead. I swear they can hear you bite a potato chip. There’s a pair of blue-headed rainbow parrots who get away with sitting closer because they are so pretty. They climb right onto the table and take packets of sugar out of the cannister, tearing them open and eating the sugar hungrily. When I berated one, she looked at me with her pretty head cocked to the side as if to say, “Well, you people took all the flowers away. What do you want us to eat?”

There are flowers, still, in the gardens nearby. Sydney people did well with their lottery and their dreams. The construction workers (and all the others) who built that big bending white House put their backs into something special. Hanging on a strap in a crowded bus in Sydney traffic or sitting thousands of kilometres away, contemplating over desert sands, the Opera House is that rare man-made thing that elevates the spirit to see or think of it.