Big Flag Day at Home

/I'm writing this on Australia Day. Among Indigenous people it is sometimes called Invasion Day or Survival Day. It commemorates the raising of the British flag in 1788 near present-day Sydney, after Captain James Cook claimed the island of Australia for the British Crown eighteen years earlier. I have mixed feelings about the day. It’s the birthday of my cousin-sister and my god-daughter – both of them Goori and women to celebrate on this day. I’m grateful to have a day off work and appreciate my colleagues who keep working today. But in the bigger picture, I abhor nationalism, any kind of dogma and jingoism. When I was a child, of course, I quite liked all those things. I remember well having a nice feeling about seeing the red, white and blue Australian flag raised when I was about nine years old.

At that age, like most intelligent girls, I knew almost everything. I felt superior to most adults and wondered why they seemed to suffer so much. A lot of my sense of snobbish superiority came from the question of work. I didn’t understand why so many adults were doing work that caused them suffering. You see, I was a bright child who was told she could be anything she wanted to be, and I believed it. Being a pop star or an actress looked like the easiest jobs, so I thought I would do one of those. I sang myself to sleep most nights with fantasies of adoration and easy wealth. I adapted the Lord’s Prayer — which I understood that you had to say to avoid hell — to suit my actual desires. I was honest enough to leave out, ‘Thy will be done’, most nights, because I wasn’t sure I trusted God to know what was best for me. I visualised a chest overflowing with jewels and asked God to make me richer than the Queen and as beautiful as Ginger on Gilligan’s Island. You can see I was quite sheltered.

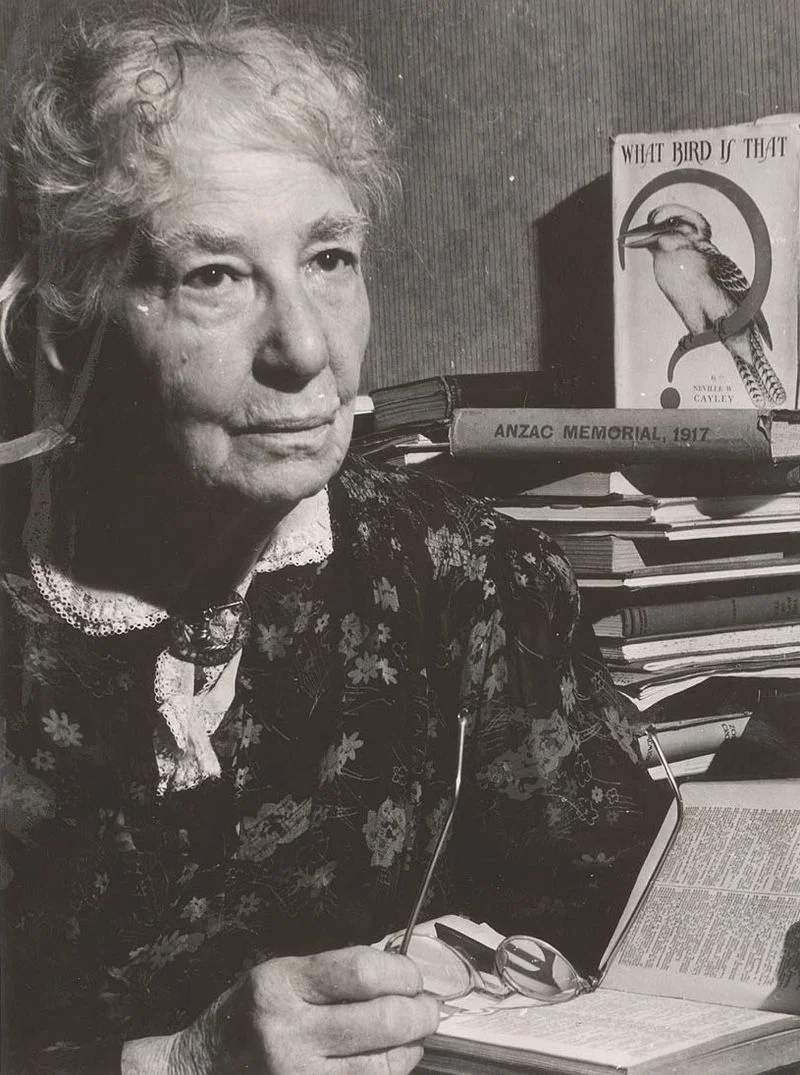

At school we had ‘houses’ — kind of a set of four sporting clubs the teachers made up — at primary school. In a sweet way, the houses were named after poets. Mine was Gilmour, named after Dame Mary Gilmour. I don’t remember any of her poems, but I do recall finding it interesting that my sporting house was named after a wizened lady. Yellow was our colour – I mainly recall it as hand-cut streamers of crepe paper. Patterson, which had red, seemed to be the more aggressive house and seemed to win more often. My best friend Helen was in Patterson and (like almost everyone) was more athletic than me.

There was a lot of standing around in blazing sun on ashphalt at school in those days, at daily assemblies, where the sixth grade teacher (the deputy principal) would shout us into a fearful stillness and obedience. In a way, he made me glad I was still small. He made me not want to grow up to fifth grade, if it meant being in his class. Our school was a rapidly growing one — my parents’ house was established by my father on a virgin block carved out of the bush — part of a development on the outer edge of Sydney in the mid-sixties. The asphalt playground was new and smelly, prone to melt into tar in the summer. The tar ended up, with balls of gravel, like a tattoo under the skin of our tender little knees.

The playing field was baked clay and stony. There were years-long struggles to establish any kind of grass through my childhood. Eventually some spikey African weed was established there. I had happy moments on my belly watching the ants explore the blades. And always that blazing sun, considered good for children in the days before we understood skin cancer, when all the fair ones wanted to be brown. And perhaps, I thought, the brown ones wanted the world to be fair.

My parents have always been sporting people, as all Australians should be. My mother is prone to barrack for the underdog in any given event and would be uncomfortable, I think, supporting a team that won too often.

Probably because of the family values, I am prone to feel that way about countries. The British who landed here on this day in 1770 won the battles too often. As I grew and travelled, I understood that there was a class of people who used their red, white and blue flag as an emblem when they went to kidnap South Sea Islanders for semi-slavery on sugar plantations in the Australian north or to recruit its young people to fight in far-away wars for Empire that involved a lot of cruelty in more blazing sun or frozen, bloody mud. I thought about flags and anthems quite a lot. I was about 10 years old when ‘Advance Australia Fair’ became the national anthem and I worried about my relations who were not fair-skinned, feeling them excluded.

Living in the USA as a teen, I stood with my hand over my heart at sporting events and enjoyed singing the stirring refrain of their anthem. I even pledged allegiance to their flag at school there each morning.

I got a trophy for being a vocal supporter of our school team in the year that year, the only sporting trophy I ever got (and the only one I am likely to get). Our girls team had a warm-hearted small-town coach who understood that there was healing in being included, especially for the chubby ones with short legs. I still enjoy yelling at the basketball.

But that feeling of relating to people in my team colours who were athletic and powerful in a way that somehow spoke for me — because of where I was born, who I was born to or where I live — got broken somehow along the way. Living in a mixed-race family, travelling to America for a year, travelling Asia late in my teens and spending time in remote Aboriginal communities has made me see how arbitrary these tokens can be.

In the place where that sense of national pride used to live, I have a feeling of compassion and connection to humanity and our planet. Especially I feel compassion and fellow-feeling with the people from the small countries and the marginalised teams that almost never win. I know I’m not alone in that.

So today, some of my countrymen may want to pretend they are friends of the British Empire and stand on the sun scorched grass — admittedly softer now and with hats — playing that slow-baked game called cricket — the pace of which accommodates inebriation and lethargy so well. I understand the feelings of my countrymen who are deeply ambivalent about the commemoration of James Cook’s landing down in the southeast 247 years ago, where all of this business started. I’m still rooting for the underdog, as my American friends would say. I feel like wearing a t-shirt with a flag from Tuvalu. But instead I'll stay inside, stay cool and rest. I am watching and waiting for this country to change.

Thumbnail: Together We Create' Pic by My Life Through A Lens